Hawaii’s vibrant mythology is populated by violent, emotional gods. But behind the fantasy could lie clues to the real volcanic events which – scientists now think – inspired them.

Ten centuries ago, the small group of Polynesian sailors who first glimpsed the Hawaiian Islands must have sensed the miraculous; a thousand miles from home, the Pacific had thrown them a lifeline. What they saw when they landed, though, confirmed the supernatural: On this lone outpost in an endless ocean, the ground was alive.

In 1790, Captain Cook became the first Westerner to meet – and be killed by – the inhabitants of the “Sandwich Islands”. Thirty years later, another Englishman – William Ellis, a missionary – spoke to them in their own tongue. No hatchets this time. Instead, they showed him their volcano – the immense, lava-scarred pit of Mount Kilauea – and told him stories; about a mythology revolving around the lava goddess Pele: Jealous, volatile – eruptive.

Volcanologists aren’t used to wading through poetic metaphor; but when Don Swanson – a former director of the observatory which (somewhat precariously) overlooks Kilauea – read Ellis’ accounts, he saw more than just superstition. He saw a record.

His volcanologist’s eye was drawn to one tale in particular. Pele had fallen in love. Steaming in her pit atop Kilauea, she demanded that her sister, Hi’iaka, fetch the object of her affections from his island home in the North. His name was Lohi’au, and he doesn’t come out of this well. Hi’iaka agreed, on one condition – that her sister keep her fires away from a grove of flowering trees that she loved. She excelled, bringing Lohi’au first back to life, and then back to Kilauea. But she took too long. Pele’s temper had flared (nobody said volcanoes were reasonable), and Hi’iaka returned to find her treasured forest ablaze. But her sister wasn’t finished. The goddess then murdered Lohi’au, casting his body into the depths of her volcano. In response, Hi’iaka began to dig. Frantically. Rocks were flying out of the crater; she delved so deep, she was warned that if she didn’t stop, she would hit water, and put out Pele’s fire.

Burning forests. Spitting craters. Write what you know, I suppose – even if you don’t have writing.

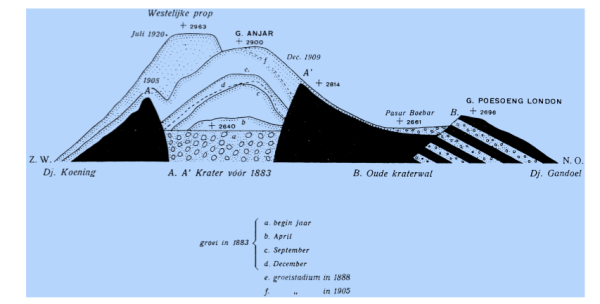

It doesn’t take a huge leap to imagine, as Swanson did, that the story of Hi’iaka’s burning forest might be echoing an ancient lava flow. But why would something as dull as a lava flow (of all things!) have diffused into myth? They’re weekly occurrences on the big island, after all. Perhaps, though, there had been one worth remembering. In the 1980s, a group of geologists discovered a flow that had been emitted from an extinct vent on Kilauea’s East flank, sometime in the 15th century. It was huge; the lava had reached the sea, more than 40 km away. Its length, though, wasn’t the only thing which caught Swanson’s eye. Through 14C analysis, he pinpointed the exact year that the flow had begun – 1410. Almost unbelivably, the end date was 1470: This single, gigantic stream of basalt had persisted for three generations. It would have changed the landscape forever; enough, perhaps, to etch itself into legend.

Incredibly, though, the final act might be hiding something even bigger. Hi’iaka’s furious digging, Swanson realised, might be describing the single biggest volcanic upheaval to have happened at Hawaii since humans arrived.

It’s a cracking piece of detective work. But also a fascinating insight into how myths begin. Swanson’s respectful treatment of the story of Pele allowed him to see it for what it partly was: a theory. Formed by people like us, striving to explain the incredible; a best guess at a time when the accessible Earth ended at the surface. Anything below, like the unknown void above the stars, was given over to the gods.

References

Swanson, D. (2008) Hawaiian oral tradition describes 400 years of volcanic activity at Kilauea. J. Volc. Geotherm. Res. 176; 427-431